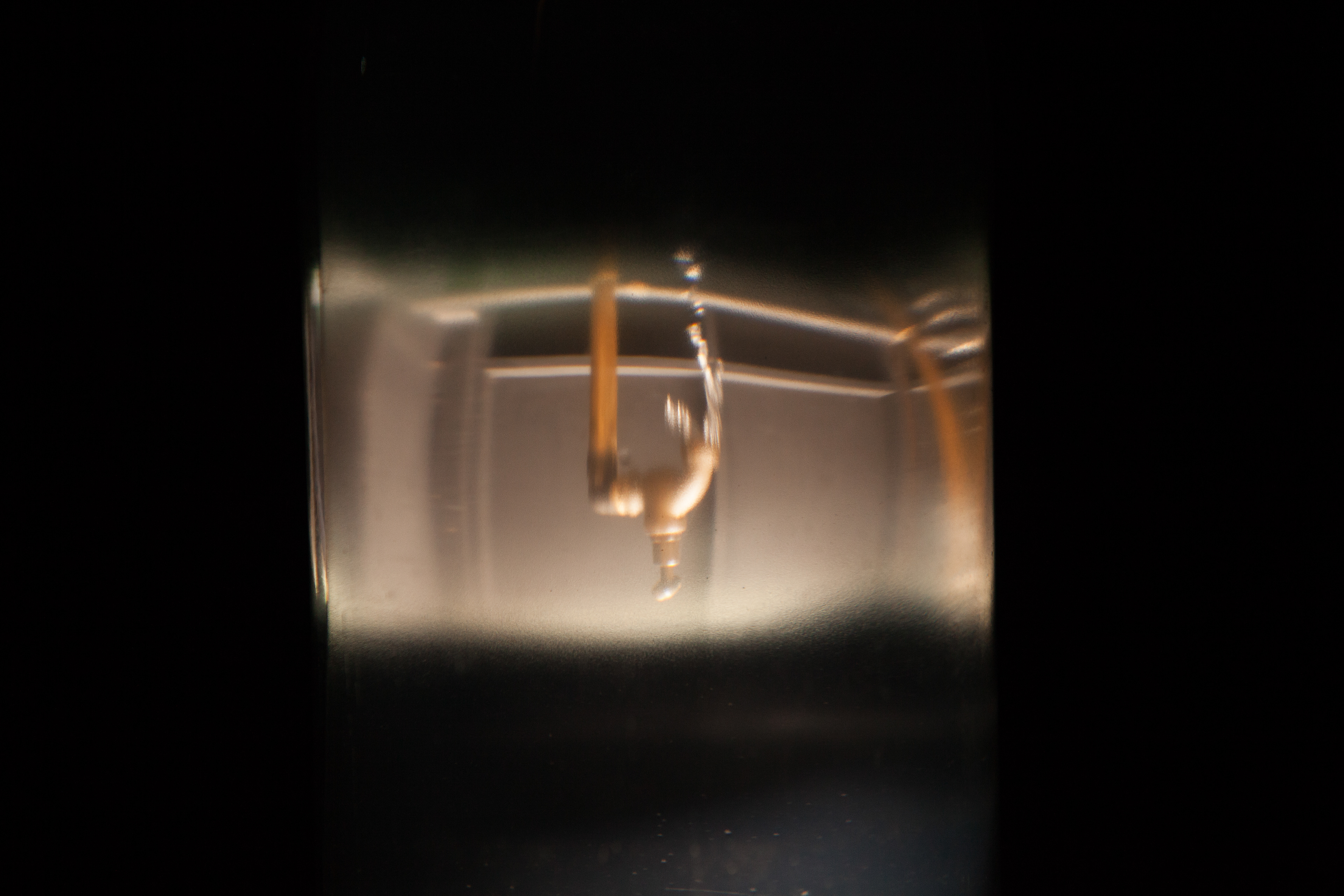

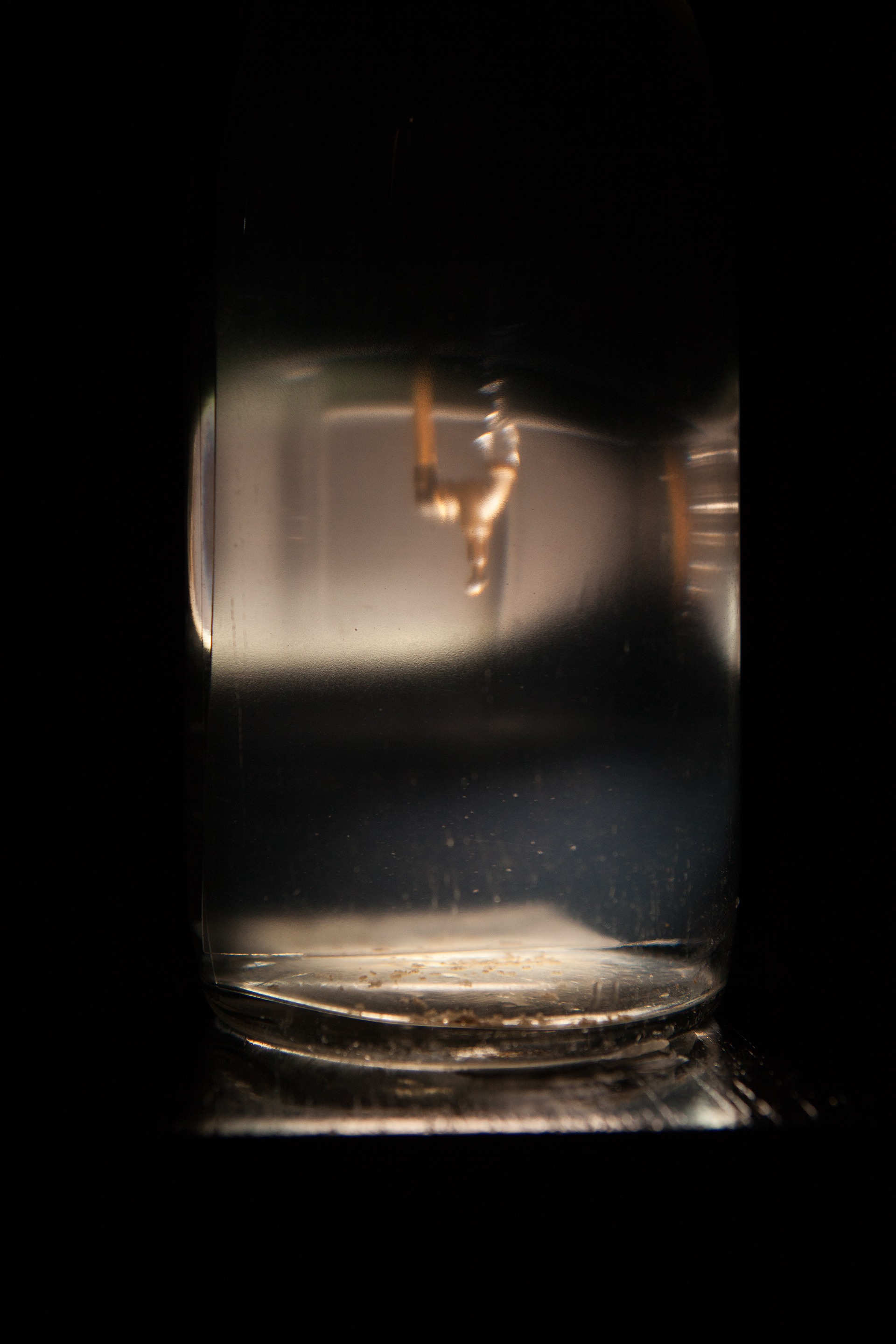

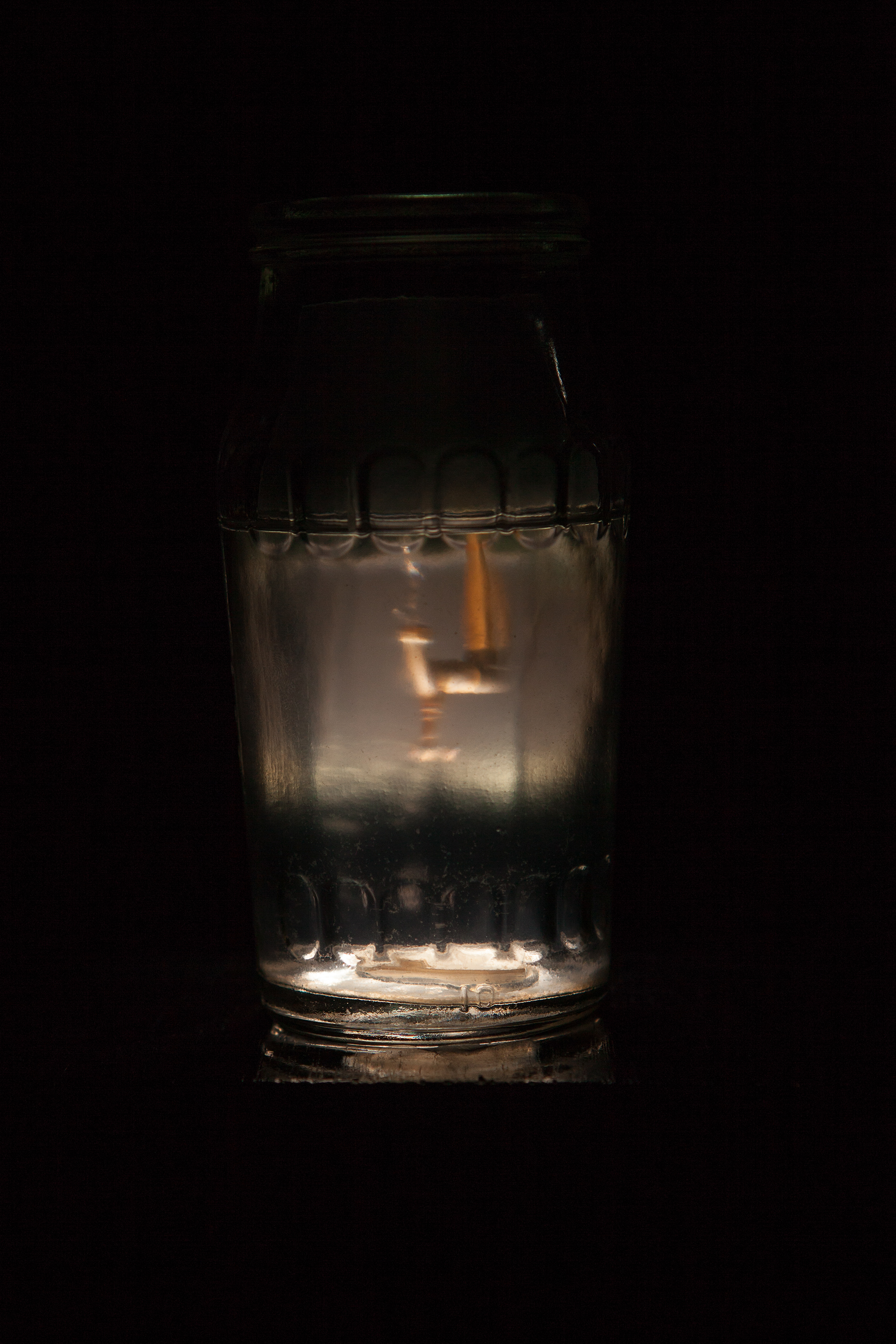

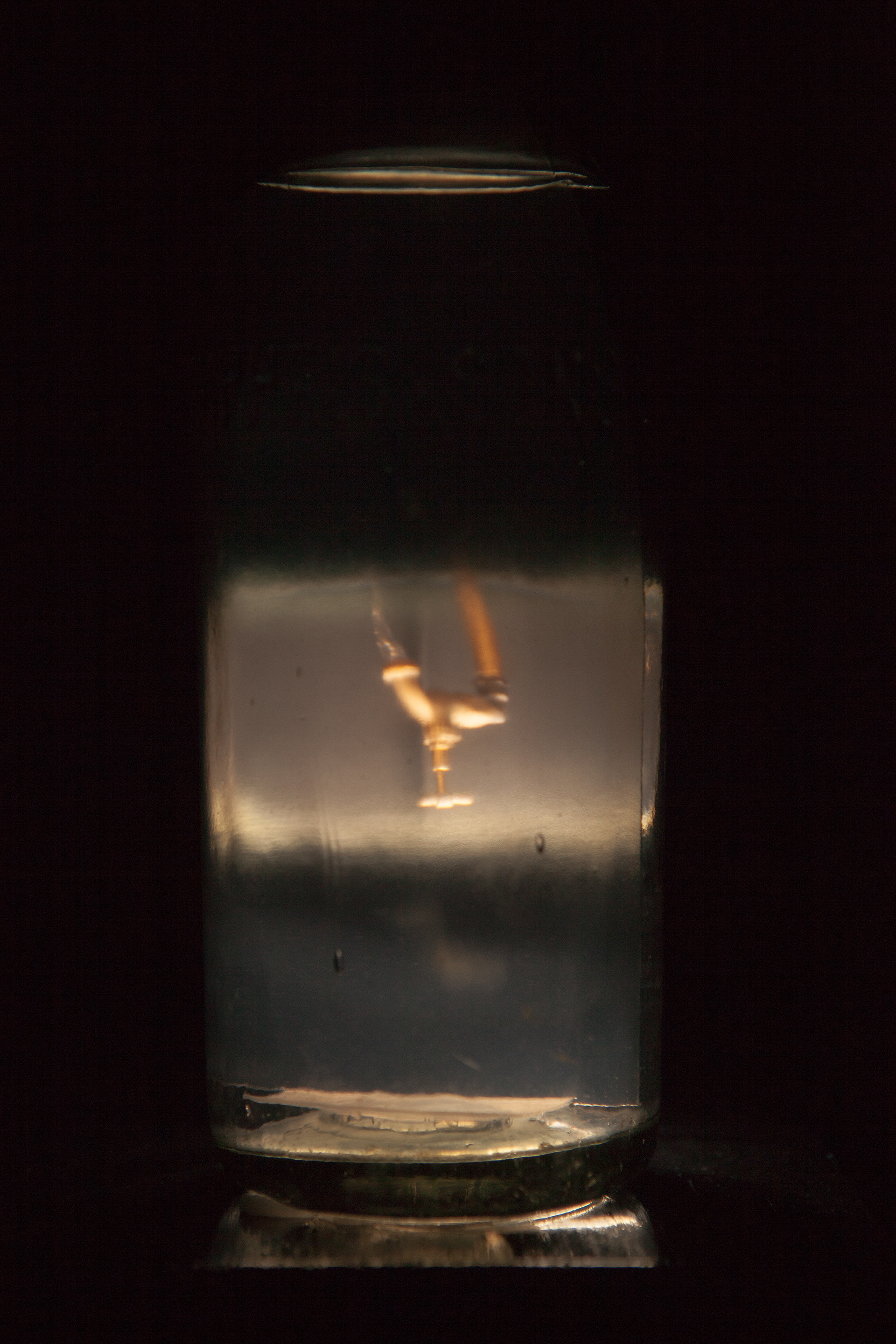

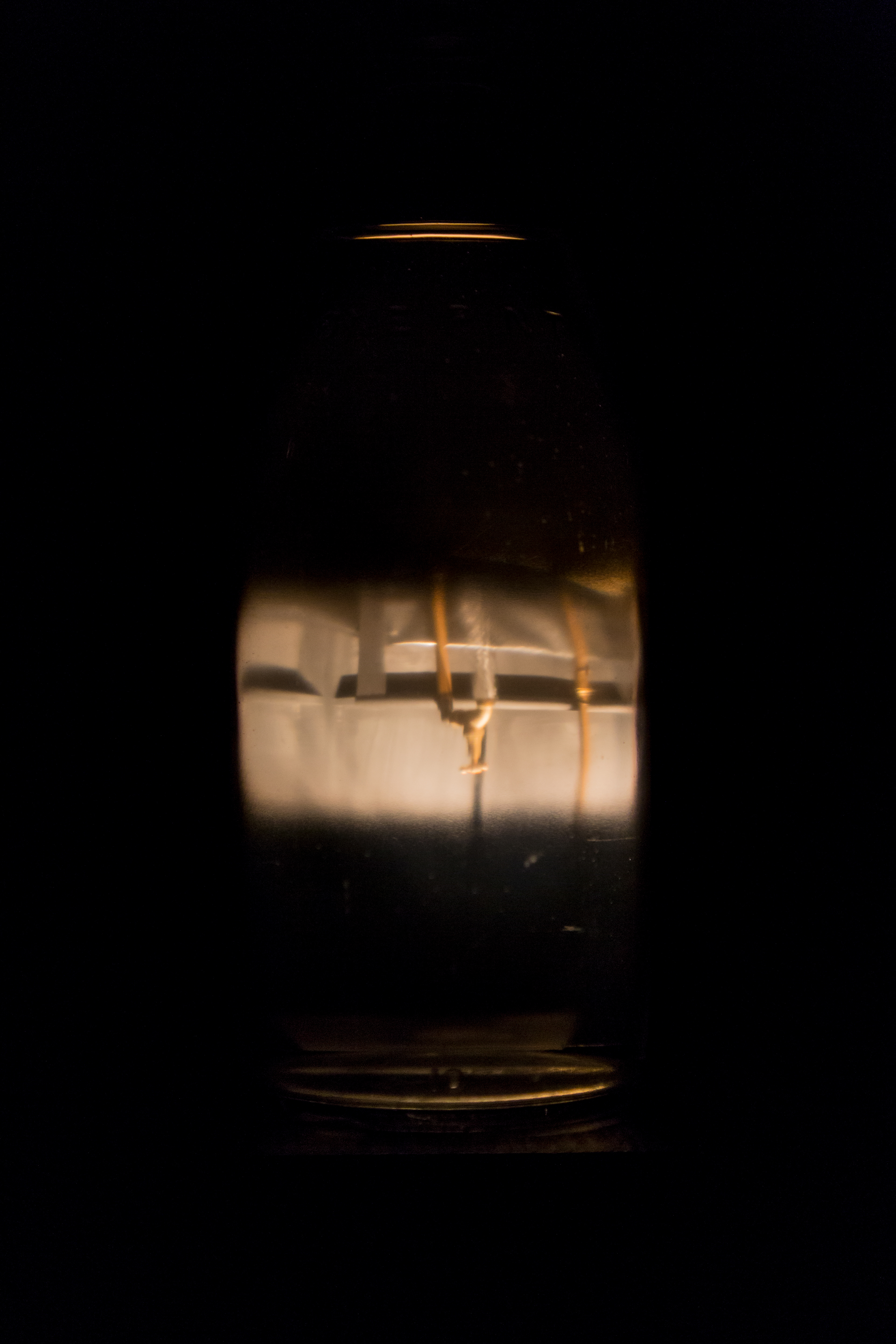

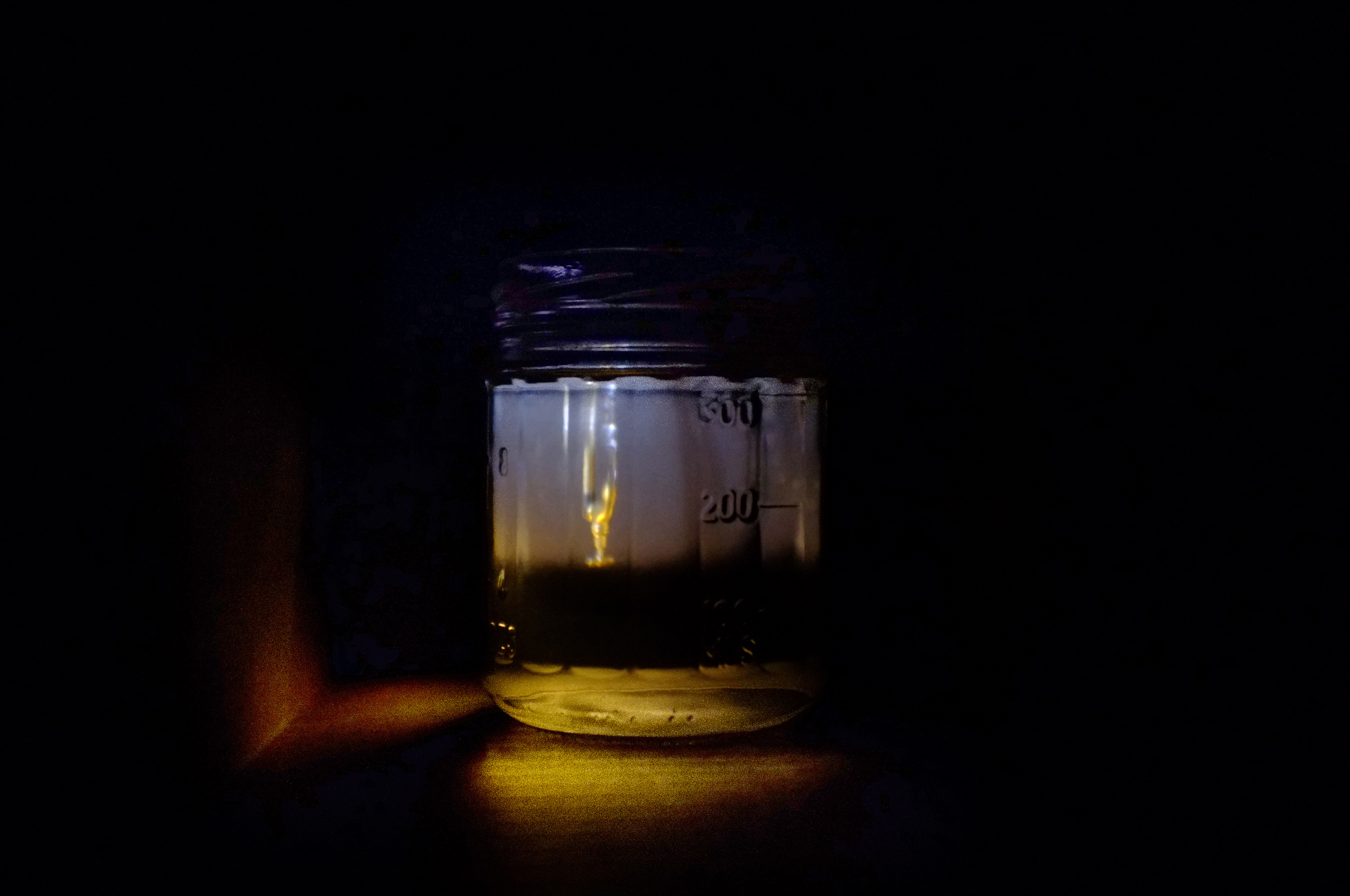

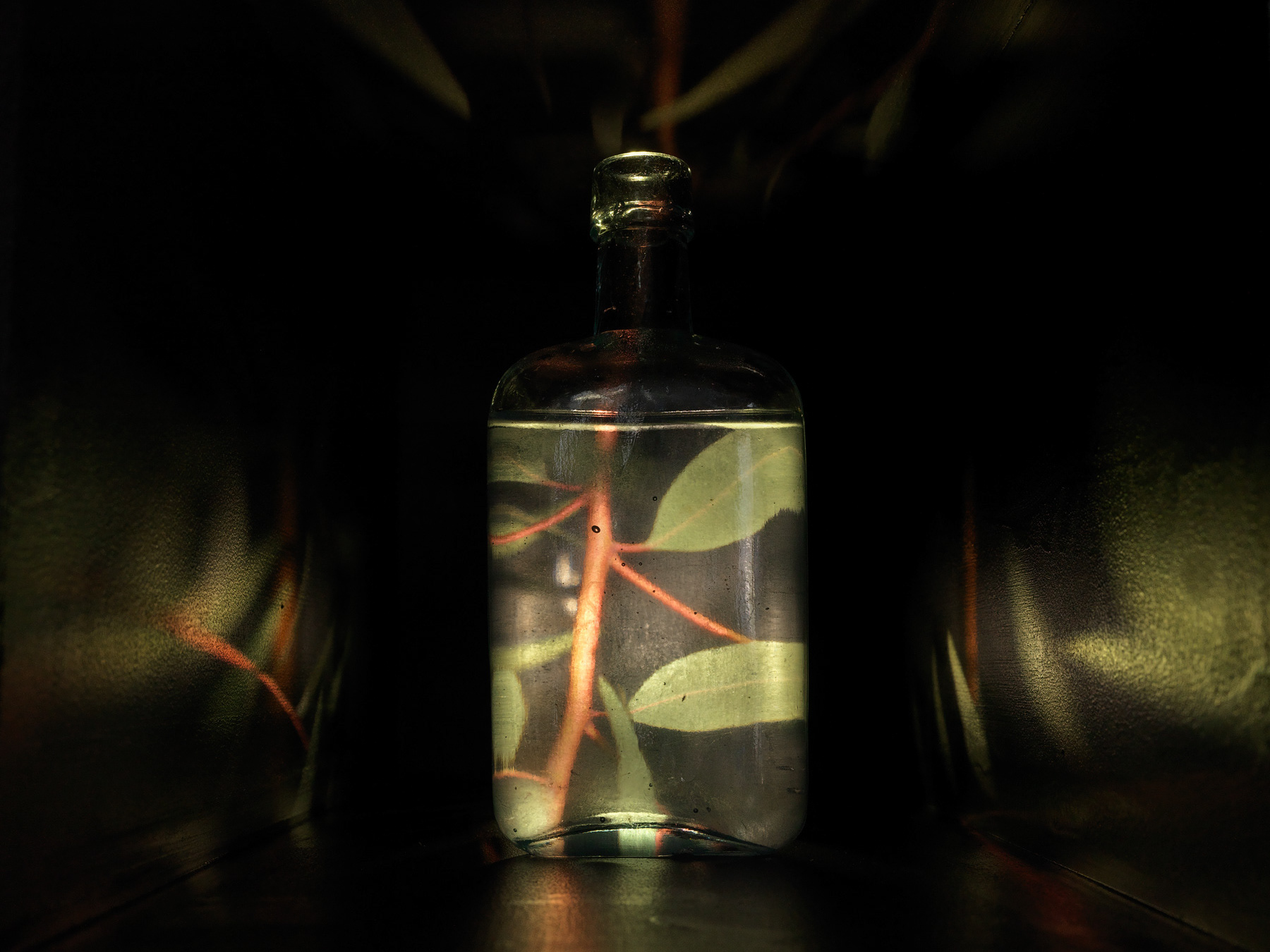

Documentation inside the installation of Everything flows, nothing remains I at the Adelaide Experimental Art Foundation. Visitors entered a darkened space and witnessed taps seemingly continuously running water upside down inside glass bottles and jars. The taps and pump were hidden in the back of the structure and projected into the bottles via glass lenses.

Everything flows, nothing remains I and II, found bottles, jars and garden taps, Murray River and Adelaide tap water, pump, lenses, fabric, timber and mixed media. 240 x 180 x 420 cm (Adelaide Experimental Art Foundation) and 240 x 120 x 330 cm (Murray Bridge Regional Gallery. Photography: Sam Roberts